Philosophy of Religion

Chapter 2. Religions of the World

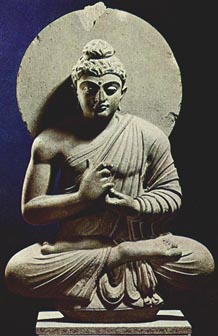

Section 4. Buddhism

· THE ABSOLUTE: what do the believers hold as most important? What is the ultimate source of value and significance? For many, but not all religions, this is given some form of agency and portrayed as a deity (deities). It might be a concept or ideal as well as a figure.

· THE WORLD: What does the belief system say about the world? Its origin? its relation to the Absolute? Its future?

· HUMANS: Where do they come from? How do they fit into the general scheme of things? What is their destiny or future?

· THE PROBLEM FOR HUMANS: What is the principle problem for humans that they must learn to deal with and solve?

· THE SOLUTION FOR HUMANS: How are humans to solve or overcome the fundamental problems ?

· COMMUNITY AND ETHICS: What is the moral code as promulgated by the religion? What is the idea of community and how humans are to live with one another?

· AN INTERPRETATION OF HISTORY: Does the religion offer an explanation for events occurring in time? Is there a single linear history with time coming to an end or does time recycle? Is there a plan working itself out in time and detectable in the events of history?

· RITUALS AND SYMBOLS: What are the major rituals, holy days, garments, ceremonies and symbols?

· LIFE AFTER DEATH: What is the explanation given for what occurs after death? Does he religion support a belief in souls or spirits which survive the death of the body? What is the belief in what occurs afterwards? Is there a resurrection of the body? Reincarnation? Dissolution? Extinction?

· RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER RELIGIONS: What is the prescribed manner in which believers are to regard other religions and the followers of other religions?

**********************************************************

For those who wish to listen to information on the world's

religions here is a listing of PODCASTS on RELIGIONS by Cynthia

Eller.

If you have iTunes on your computer just click and you will be led to the

listings.

http://phobos.apple.com/WebObjects/MZStore.woa/wa/viewPodcast?id=117762189&s=143441

Here is a link to the site for the textbook REVEALING WORLD RELIGIONS

related to which these podcasts were made.

http://thinkingstrings.com/Product/WR/index.html

************************************************************

Buddhism evolved in India. There were periods in India's past when Buddhism was dominant in India. Today less then 1% of India's population is Buddhist. Buddhism has more followers in countries east of India. Buddhism was established in about 500 BC. Buddhism began with a prince called Siddhartha Gautama. Siddhartha belonged to an aristocratic family. As a prince he had lot of wealth. He never left his palace. At some point Siddharta began to leave his palace and behold for the first time poverty, sickness and misery. After seeing this Siddharta lost interest in his spoiled life and left his palace forever and gave his rich personal belongings to the needy. He joined a group of ascetics who were searching for enlightenment. In those days people searching for enlightenment believed that this could be gained only by people who were capable of resisting their basic needs. These people almost did not eat anything and almost starved themselves to death. Siddharta also adopted this path of searching enlightenment. But at some point he came to a conclusion that this was neither the way towards enlightenment nor the spoiled life he had as a prince was the right path towards enlightenment. According to him the right path was somewhere in the middle and he called it the 'middle path'.

In order to focus on his enlightenment search, Buddha sat under a fig tree and after fighting many temptations he got his enlightenment. In his region 'enlightened' people were called Buddha. And so Siddharta was named Buddha. According to Buddha's theory life is a long suffering. The suffering is caused because of the passions people desire to accomplish. The more one desires and the less he accomplishes the more he suffers. People who do not accomplish their desirable passions in their lives will be born again to this life circle which is full of suffering and so will distant themselves from the world of no suffering - Nirvana.

To get Nirvana, one has to follow the eight-fold path which are to believe right, desire right, think right, live right, do the right efforts, think the right thoughts, behave right and to do the right meditation.

Buddhism emphasis non- violence. Buddha attacked the Brahmanic custom of animal slaughtering during religious ceremonies. Religiously the Buddhists are vegetarians. But many Indians believe that Buddha, died because he ate a sick animal. Buddhism does not have a God. But many Buddhists keep images of Buddha. Buddha is not seen as the first prophet of the religion, but as the fourth prophet of the religion.

There are two main doctrines in Buddhism, Mahayana and Hinayana. Mahayana Buddhist believe that the right path of a follower will lead to the redemption of all human beings. The Hinayana believe that each person is responsible for his own fate. Along with these doctrines there are other Buddhist beliefs like 'Zen Buddhism' from Japan and the 'Hindu Tantric Buddhism' from Tibet. Zen Buddhism is a mixture of Buddhism as it arrived from India to Japan and original Japanese beliefs. The Hindu Tantric Buddhism is a mixture of Indian Buddhism and original Tibetian beliefs which existed among the Tibetians before the arrival of Buddhism in Tibet, among it magic, ghosts and tantras (meaningless mystical sentences).©Aharon Daniel Israel 1999-2000

I. Introduction

Buddhism, a major world religion, founded in northeastern India and based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, who is known as the Buddha, or Enlightened One. See Buddha.

Originating as a monastic movement within the dominant Brahman tradition of the day, Buddhism quickly developed in a distinctive direction. The Buddha not only rejected significant aspects of Hindu philosophy, but also challenged the authority of the priesthood, denied the validity of the Vedic scriptures, and rejected the sacrificial cult based on them. Moreover, he opened his movement to members of all castes, denying that a person's spiritual worth is a matter of birth. See Hinduism.

Buddhism today is divided into two major branches known to their respective followers as Theravada, the Way of the Elders, and Mahayana, the Great Vehicle. Followers of Mahayana refer to Theravada using the derogatory term Hinayana, the Lesser Vehicle.

Buddhism has been significant not only in India but also in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), and Laos, where Theravada has been dominant; Mahayana has had its greatest impact in China, Japan, Taiwan, Tibet, Nepal, Mongolia, Korea, and Vietnam, as well as in India. The number of Buddhists worldwide has been estimated at between 150 and 300 million. The reasons for such a range are twofold: Throughout much of Asia religious affiliation has tended to be nonexclusive; and it is especially difficult to estimate the continuing influence of Buddhism in Communist countries such as China.

II. Origins

As did most major faiths, Buddhism developed over many years.

A. Buddha's Life

No complete biography of the Buddha was compiled until centuries after his death; only fragmentary accounts of his life are found in the earliest sources. Western scholars, however, generally agree on 563 BC as the year of his birth.

Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, was born in Lumbini near the present Indian-Nepal border, the son of the ruler of a petty kingdom. According to legend, at his birth sages recognized in him the marks of a great man with the potential to become either a sage or the ruler of an empire. The young prince was raised in sheltered luxury, until at the age of 29 he realized how empty his life to this point had been. Renouncing earthly attachments, he embarked on a quest for peace and enlightenment, seeking release from the cycle of rebirths. For the next few years he practiced Yoga and adopted a life of radical asceticism.

Eventually he gave up this approach as fruitless and instead adopted a middle path between the life of indulgence and that of self-denial. Sitting under a bo tree, he meditated, rising through a series of higher states of consciousness until he attained the enlightenment for which he had been searching. Once having known this ultimate religious truth, the Buddha underwent a period of intense inner struggle. He began to preach, wandering from place to place, gathering a body of disciples, and organizing them into a monastic community known as the sangha. In this way he spent the rest of his life.

B. Buddha's Teachings

The Buddha was an oral teacher; he left no written body of thought. His beliefs were codified by later followers.

1. The Four Noble Truths

At the core of the Buddha's enlightenment was the realization of the Four Noble Truths: (1) Life is suffering. This is more than a mere recognition of the presence of suffering in existence. It is a statement that, in its very nature, human existence is essentially painful from the moment of birth to the moment of death. Even death brings no relief, for the Buddha accepted the Hindu idea of life as cyclical, with death leading to further rebirth. (2) All suffering is caused by ignorance of the nature of reality and the craving, attachment, and grasping that result from such ignorance. (3) Suffering can be ended by overcoming ignorance and attachment. (4) The path to the suppression of suffering is the Noble Eightfold Path, which consists of right views, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right-mindedness, and right contemplation. These eight are usually divided into three categories that form the cornerstone of Buddhist faith: morality, wisdom, and samadhi, or concentration.

2. Anatman

Buddhism analyzes human existence as made up of five aggregates or "bundles" (skandhas): the material body, feelings, perceptions, predispositions or karmic tendencies, and consciousness. A person is only a temporary combination of these aggregates, which are subject to continual change. No one remains the same for any two consecutive moments. Buddhists deny that the aggregates individually or in combination may be considered a permanent, independently existing self or soul (atman). Indeed, they regard it as a mistake to conceive of any lasting unity behind the elements that constitute an individual. The Buddha held that belief in such a self results in egoism, craving, and hence in suffering. Thus he taught the doctrine of anatman, or the denial of a permanent soul. He felt that all existence is characterized by the three marks of anatman (no soul), anitya (impermanence), and dukkha (suffering). The doctrine of anatman made it necessary for the Buddha to reinterpret the Indian idea of repeated rebirth in the cycle of phenomenal existence known as samsara. To this end he taught the doctrine of pratityasamutpada, or dependent origination. This 12-linked chain of causation shows how ignorance in a previous life creates the tendency for a combination of aggregates to develop. These in turn cause the mind and senses to operate. Sensations result, which lead to craving and a clinging to existence. This condition triggers the process of becoming once again, producing a renewed cycle of birth, old age, and death. Through this causal chain a connection is made between one life and the next. What is posited is a stream of renewed existences, rather than a permanent being that moves from life to life—in effect a belief in rebirth without transmigration.

3. Karma

Closely related to this belief is the doctrine of karma. Karma consists of a person's acts and their ethical consequences. Human actions lead to rebirth, wherein good deeds are inevitably rewarded and evil deeds punished. Thus, neither undeserved pleasure nor unwarranted suffering exists in the world, but rather a universal justice. The karmic process operates through a kind of natural moral law rather than through a system of divine judgment. One's karma determines such matters as one's species, beauty, intelligence, longevity, wealth, and social status. According to the Buddha, karma of varying types can lead to rebirth as a human, an animal, a hungry ghost, a denizen of hell, or even one of the Hindu gods.

Although never actually denying the existence of the gods, Buddhism denies them any special role. Their lives in heaven are long and pleasurable, but they are in the same predicament as other creatures, being subject eventually to death and further rebirth in lower states of existence. They are not creators of the universe or in control of human destiny, and Buddhism denies the value of prayer and sacrifice to them. Of the possible modes of rebirth, human existence is preferable, because the deities are so engrossed in their own pleasures that they lose sight of the need for salvation. Enlightenment is possible only for humans.

4. Nirvana

The ultimate goal of the Buddhist path is release from the round of phenomenal existence with its inherent suffering. To achieve this goal is to attain nirvana, an enlightened state in which the fires of greed, hatred, and ignorance have been quenched. Not to be confused with total annihilation, nirvana is a state of consciousness beyond definition. After attaining nirvana, the enlightened individual may continue to live, burning off any remaining karma until a state of final nirvana (parinirvana) is attained at the moment of death.

In theory, the goal of nirvana is attainable by anyone, although it is a realistic goal only for members of the monastic community. In Theravada Buddhism an individual who has achieved enlightenment by following the Eightfold Path is known as an arhat, or worthy one, a type of solitary saint.

For those unable to pursue the ultimate goal, the proximate goal of better rebirth through improved karma is an option. This lesser goal is generally pursued by lay Buddhists in the hope that it will eventually lead to a life in which they are capable of pursuing final enlightenment as members of the sangha.

The ethic that leads to nirvana is detached and inner-oriented. It involves cultivating four virtuous attitudes, known as the Palaces of Brahma: loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. The ethic that leads to better rebirth, however, is centered on fulfilling one's duties to society. It involves acts of charity, especially support of the sangha, as well as observance of the five precepts that constitute the basic moral code of Buddhism. The precepts prohibit killing, stealing, harmful language, sexual misbehavior, and the use of intoxicants. By observing these precepts, the three roots of evil—lust, hatred, and delusion—may be overcome.

III. Early Development

Shortly before his death, the Buddha refused his disciples' request to appoint a successor, telling his followers to work out their own salvation with diligence. At that time Buddhist teachings existed only in oral traditions, and it soon became apparent that a new basis for maintaining the community's unity and purity was needed. Thus, the monastic order met periodically to reach agreement on matters of doctrine and practice. Four such meetings have been focused on in the traditions as major councils.

A. Major Councils

The first council was held at Rajagrha (present-day Rajgir) immediately after the Buddha's death. Presided over by a monk named Mahakasyapa, its purpose was to recite and agree on the Buddha's actual teachings and on proper monastic discipline.

About a century later, a second great council is said to have met at Vaishali. Its purpose was to deal with ten questionable monastic practices—the use of money, the drinking of palm wine, and other irregularities—of monks from the Vajjian Confederacy; the council declared these practices unlawful. Some scholars trace the origins of the first major split in Buddhism to this event, holding that the accounts of the council refer to the schism between the Mahasanghikas, or Great Assembly, and the stricter Sthaviras, or Elders. More likely, however, the split between these two groups became formalized at another meeting held some 37 years later as a result of the continued growth of tensions within the sangha over disciplinary issues, the role of the laity, and the nature of the arhat.

In time, further subdivisions within these groups resulted in 18 schools that differed on philosophical matters, religious questions, and points of discipline. Of these 18 traditional sects, only Theravada survives.

The third council at Pataliputra (present-day Patna) was called by King Ashoka in the 3rd century BC. Convened by the monk Moggaliputta Tissa, it was held in order to purify the sangha of the large number of false monks and heretics who had joined the order because of its royal patronage. This council refuted the offending viewpoints and expelled those who held them. In the process, the compilation of the Buddhist scriptures (Tipitaka) was supposedly completed, with the addition of a body of subtle philosophy (abhidharma) to the doctrine (dharma) and monastic discipline (vinaya) that had been recited at the first council. Another result of the third council was the dispatch of missionaries to various countries.

A fourth council, under the patronage of King Kanishka, was held about AD 100 at Jalandhar or in Kashmir. Both branches of Buddhism may have participated in this council, which aimed at creating peace among the various sects, but Theravada Buddhists refuse to recognize its authenticity.

B. Formation of Buddhist Literature

For several centuries after the death of the Buddha, the scriptural traditions recited at the councils were transmitted orally. These were finally committed to writing about the 1st century BC. Some early schools used Sanskrit for their scriptural language. Although individual texts are extant, no complete canon has survived in Sanskrit. In contrast, the full canon of the Theravadins survives in Pali, which was apparently a popular dialect derived from Sanskrit.

The Buddhist canon is known in Pali as the Tipitaka (Tripitaka in Sanskrit), meaning "Three Baskets," because it consists of three collections of writings: the Sutta Pitaka (Sutra Pitaka in Sanskrit), a collection of discourses; the Vinaya Pitaka, the code of monastic discipline; and the Abhidharma Pitaka, which contains philosophical, psychological, and doctrinal discussions and classifications.

The Sutta Pitaka is primarily composed of dialogues between the Buddha and other people. It consists of five groups of texts: Digha Nikaya (Collection of Long Discourses), Majjhima Nikaya (Collection of Medium-Length Discourses), Samyutta Nikaya (Collection of Grouped Discourses), Anguttara Nikaya (Collection of Discourses on Numbered Topics), and Khuddaka Nikaya (Collection of Miscellaneous Texts). In the fifth group, the Jatakas, comprising stories of former lives of the Buddha, and the Dhammapada (Religious Sentences), a summary of the Buddha's teachings on mental discipline and morality, are especially popular.

The Vinaya Pitaka consists of more than 225 rules governing the conduct of Buddhist monks and nuns. Each is accompanied by a story explaining the original reason for the rule. The rules are arranged according to the seriousness of the offense resulting from their violation.

The Abhidharma Pitaka consists of seven separate works. They include detailed classifications of psychological phenomena, metaphysical analysis, and a thesaurus of technical vocabulary. Although technically authoritative, the texts in this collection have little influence on the lay Buddhist. The complete canon, much expanded, also exists in Tibetan and Chinese versions.

Two noncanonical texts that have great authority within Theravada Buddhism are the Milindapanha (Questions of King Milinda) and the Visuddhimagga (Path of Purification). The Milindapanha dates from about the 2nd century AD. It is in the form of a dialogue dealing with a series of fundamental problems in Buddhist thought. The Visuddhimagga is the masterpiece of the most famous of Buddhist commentators, Buddhaghosa (flourished early 5th century AD). It is a large compendium summarizing Buddhist thought and meditative practice.

Theravada Buddhists have traditionally considered the Tipitaka to be the remembered words of Siddhartha Gautama. Mahayana Buddhists have not limited their scriptures to the teachings of this historical figure, however, nor has Mahayana ever bound itself to a closed canon of sacred writings. Various scriptures have thus been authoritative for different branches of Mahayana at various periods of history. Among the more important Mahayana scriptures are the following: the Saddharmapundarika Sutra (Lotus of the Good Law Sutra, popularly known as the Lotus Sutra), the Vimalakirti Sutra, the Avatamsaka Sutra (Garland Sutra), and the Lankavatara Sutra (The Buddha's Descent to Sri Lanka Sutra), as well as a group of writings known as the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom).

C. Conflict and New Groupings

As Buddhism developed in its early years, conflicting interpretations of the master's teachings appeared, resulting in the traditional 18 schools of Buddhist thought. As a group, these schools eventually came to be considered too conservative and literal minded in their attachment to the master's message. Among them, Theravada was charged with being too individualistic and insufficiently concerned with the needs of the laity. Such dissatisfaction led a liberal wing of the sangha to begin to break away from the rest of the monks at the second council in 383 BC.

While the more conservative monks continued to honor the Buddha as a perfectly enlightened human teacher, the liberal Mahasanghikas developed a new concept. They considered the Buddha an eternal, omnipresent, transcendental being. They speculated that the human Buddha was but an apparition of the transcendental Buddha that was created for the benefit of humankind. In this understanding of the Buddha nature, Mahasanghika thought is something of a prototype of Mahayana.

1. Mahayana

The origins of Mahayana are particularly obscure. Even the names of its founders are unknown, and scholars disagree about whether it originated in southern or in northwestern India. Its formative years were between the 2nd century BC and the 1st century AD.

Speculation about the eternal Buddha continued well after the beginning of the Christian era and culminated in the Mahayana doctrine of his threefold nature, or triple "body" (trikaya). These aspects are the body of essence, the body of communal bliss, and the body of transformation. The body of essence represents the ultimate nature of the Buddha. Beyond form, it is the unchanging absolute and is spoken of as consciousness or the void. This essential Buddha nature manifests itself, taking on heavenly form as the body of communal bliss. In this form the Buddha sits in godlike splendor, preaching in the heavens. Lastly, the Buddha nature appears on earth in human form to convert humankind. Such an appearance is known as a body of transformation. The Buddha has taken on such an appearance countless times. Mahayana considers the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, only one example of the body of transformation.

The new Mahayana concept of the Buddha made possible concepts of divine grace and ongoing revelation that are lacking in Theravada. Belief in the Buddha's heavenly manifestations led to the development of a significant devotional strand in Mahayana. Some scholars have therefore described the early development of Mahayana in terms of the "Hinduization" of Buddhism.

Another important new concept in Mahayana is that of the bodhisattva or enlightenment being, as the ideal toward which the good Buddhist should aspire. A bodhisattva is an individual who has attained perfect enlightenment but delays entry into final nirvana in order to make possible the salvation of all other sentient beings. The bodhisattva transfers merit built up over many lifetimes to less fortunate creatures. The key attributes of this social saint are compassion and loving-kindness. For this reason Mahayana considers the bodhisattva superior to the arhats who represent the ideal of Theravada. Certain bodhisattvas, such as Maitreya, who represents the Buddha's loving-kindness, and Avalokitesvara or Guanyin, who represents his compassion, have become the focus of popular devotional worship in Mahayana.

2. Tantrism

By the 7th century AD a new form of Buddhism known as Tantrism (see Tantra) had developed through the blend of Mahayana with popular folk belief and magic in northern India. Similar to Hindu Tantrism, which arose about the same time, Buddhist Tantrism differs from Mahayana in its strong emphasis on sacramental action. Also known as Vajrayana, the Diamond Vehicle, Tantrism is an esoteric tradition. Its initiation ceremonies involve entry into a mandala, a mystic circle or symbolic map of the spiritual universe. Also important in Tantrism is the use of mudras, or ritual gestures, and mantras, or sacred syllables, which are repeatedly chanted and used as a focus for meditation. Vajrayana became the dominant form of Buddhism in Tibet and was also transmitted through China to Japan, where it continues to be practiced by the Shingon sect.

IV. From India Outward

Buddhism spread rapidly throughout the land of its birth. Missionaries dispatched by King Ashoka introduced the religion to southern India and to the northwest part of the subcontinent. According to inscriptions from the Ashokan period, missionaries were sent to countries along the Mediterranean, although without success.

A. Asian Expansion

King Ashoka's son Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta are credited with the conversion of Sri Lanka. From the beginning of its history there, Theravada was the state religion of Sri Lanka.

According to tradition, Theravada was carried to Myanmar from Sri Lanka during the reign of Ashoka, but no firm evidence of its presence there appears until the 5th century AD. From Myanmar, Theravada spread to the area of modern Thailand in the 6th century. It was adopted by the Thai people when they finally entered the region from southwestern China between the 12th and 14th centuries. With the rise of the Thai Kingdom, it was adopted as the state religion. Theravada was adopted by the royal house in Laos during the 14th century.

Both Mahayana and Hinduism had begun to influence Cambodia by the end of the 2nd century AD. After the 14th century, however, under Thai influence, Theravada gradually replaced the older establishment as the primary religion in Cambodia.

About the beginning of the Christian era, Buddhism was carried to Central Asia. From there it entered China along the trade routes by the early 1st century AD. Although opposed by the Confucian orthodoxy and subject to periods of persecution in 446, 574-77, and 845, Buddhism was able to take root, influencing Chinese culture and, in turn, adapting itself to Chinese ways. The major influence of Chinese Buddhism ended with the great persecution of 845, although the meditative Zen, or Ch'an (from Sanskrit dhyana,"meditation"), sect and the devotional Pure Land sect continued to be important.

From China, Buddhism continued its spread. Confucian authorities discouraged its expansion into Vietnam, but Mahayana's influence there was beginning to be felt as early as AD 189. According to traditional sources, Buddhism first arrived in Korea from China in AD 372. From this date Korea was gradually converted through Chinese influence over a period of centuries.

Buddhism was carried into Japan from Korea. It was known to the Japanese earlier, but the official date for its introduction is usually given as AD 552. It was proclaimed the state religion of Japan in 594 by Prince Shotoku.

Buddhism was first introduced into Tibet through the influence of foreign wives of the king, beginning in the 7th century AD. By the middle of the next century, it had become a significant force in Tibetan culture. A key figure in the development of Tibetan Buddhism was the Indian monk Padmasambhava, who arrived in Tibet in 747. His main interest was the spread of Tantric Buddhism, which became the primary form of Buddhism in Tibet. Indian and Chinese Buddhists vied for influence, and the Chinese were finally defeated and expelled from Tibet near the end of the 8th century.

Some seven centuries later Tibetan Buddhists had adopted the idea that the abbots of its great monasteries were reincarnations of famous bodhisattvas. Thereafter, the chief of these abbots became known as the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lamas ruled Tibet as a theocracy from the middle of the 17th century until the seizure of Tibet by China in 1950. See Tibetan Buddhism.

B. New Sects

Several important new sects of Buddhism developed in China and flourished there and in Japan, as well as elsewhere in East Asia. Among these, Ch'an, or Zen, and Pure Land, or Amidism, were most important.

Zen advocated the practice of meditation as the way to a sudden, intuitive realization of one's inner Buddha nature. Founded by the Indian monk Bodhidharma, who arrived in China in 520, Zen emphasizes practice and personal enlightenment rather than doctrine or the study of scripture.See Zen.

Instead of meditation, Pure Land stresses faith and devotion to the Buddha Amitabha, or Buddha of Infinite Light, as a means to rebirth in an eternal paradise known as the Pure Land. Rebirth in this Western Paradise is thought to depend on the power and grace of Amitabha, rather than to be a reward for human piety. Devotees show their devotion to Amitabha with countless repetitions of the phrase "Homage to the Buddha Amitabha." Nonetheless, a single sincere recitation of these words may be sufficient to guarantee entry into the Pure Land.

A distinctively Japanese sect of Mahayana is Nichiren Buddhism, which is named after its 13th-century founder. Nichiren believed that the Lotus Sutra contains the essence of Buddhist teaching. Its contents can be epitomized by the formula "Homage to the Lotus Sutra," and simply by repeating this formula the devotee may gain enlightenment.

V. Institutions and Practices

Differences occur in the religious obligations and observances both within and between the sangha and the laity.

A. Monastic Life

From the first, the most devoted followers of the Buddha were organized into the monastic sangha. Its members were identified by their shaved heads and robes made of unsewn orange cloth. The early Buddhist monks, or bhikkus, wandered from place to place, settling down in communities only during the rainy season when travel was difficult. Each of the settled communities that developed later was independent and democratically organized. Monastic life was governed by the rules of the Vinaya Sutra, one of the three canonical collections of scripture. Fortnightly, a formal assembly of monks, the uposatha, was held in each community. Central to this observance was the formal recitation of the Vinaya rules and the public confession of all violations. The sangha included an order for nuns as well as for monks, a unique feature among Indian monastic orders. Theravadan monks and nuns were celibate and obtained their food in the form of alms on a daily round of the homes of lay devotees. The Zen school came to disregard the rule that members of the sangha should live on alms. Part of the discipline of this sect required its members to work in the fields to earn their own food. In Japan the popular Shin school, a branch of Pure Land, allows its priests to marry and raise families. Among the traditional functions of the Buddhist monks are the performance of funerals and memorial services in honor of the dead. Major elements of such services include the chanting of scripture and transfer of merit for the benefit of the deceased.

B. Lay Worship

Lay worship in Buddhism is primarily individual rather than congregational. Since earliest times a common expression of faith for laity and members of the sangha alike has been taking the Three Refuges, that is, reciting the formula "I take refuge in the Buddha. I take refuge in the dharma. I take refuge in the sangha." Although technically the Buddha is not worshiped in Theravada, veneration is shown through the stupa cult. A stupa is a domelike sacred structure containing a relic. Devotees walk around the dome in a clockwise direction, carrying flowers and incense as a sign of reverence. The relic of the Buddha's tooth in Kandy, Sri Lanka, is the focus of an especially popular festival on the Buddha's birthday. The Buddha's birthday is celebrated in every Buddhist country. In Theravada this celebration is known as Vaisakha, after the month in which the Buddha was born. Popular in Theravada lands is a ceremony known as pirit, or protection, in which readings from a collection of protective charms from the Pali canon are conducted to exorcise evil spirits, cure illness, bless new buildings, and achieve other benefits.

In Mahayana countries ritual is more important than in Theravada. Images of the buddhas and bodhisattvas on temple altars and in the homes of devotees serve as a focus for worship. Prayer and chanting are common acts of devotion, as are offerings of fruit, flowers, and incense. One of the most popular festivals in China and Japan is the Ullambana Festival, in which offerings are made to the spirits of the dead and to hungry ghosts. It is held that during this celebration the gates to the other world are open so that departed spirits can return to earth for a brief time.

VI. Buddhism Today

One of the lasting strengths of Buddhism has been its ability to adapt to changing conditions and to a variety of cultures. It is philosophically opposed to materialism, whether of the Western or the Marxist-Communist variety. Buddhism does not recognize a conflict between itself and modern science. On the contrary, it holds that the Buddha applied the experimental approach to questions of ultimate truth.

In Thailand and Myanmar, Buddhism remains strong. Reacting to charges of being socially unconcerned, its monks have become involved in various social welfare projects. Although Buddhism in India largely died out between the 8th and 12th centuries AD, resurgence on a small scale was sparked by the conversion of 3.5 million former members of the untouchable caste, under the leadership of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, beginning in 1956. A similar renewal of Buddhism in Sri Lanka dates from the 19th century.

Under the Communist republics in Asia, Buddhism has faced a more difficult time. In China, for example, it continues to exist, although under strict government regulation and supervision. Many monasteries and temples have been converted to schools, dispensaries, and other public use. Monks and nuns have been required to undertake employment in addition to their religious functions. In Tibet, the Chinese, after their takeover and the escape of the Dalai Lama and other Buddhist officials into India in 1959, attempted to undercut Buddhist influence.

Only in Japan since World War II have truly new Buddhist movements arisen. Notable among these is Soka Gakkai, the Value Creation Society, a lay movement associated with Nichiren Buddhism. It is noted for its effective organization, aggressive conversion techniques, and use of mass media, as well as for its nationalism. It promises material benefit and worldly happiness to its believers. Since 1956 it has been involved in Japanese politics, running candidates for office under the banner of its Komeito, or Clean Government Party.

Growing interest in Asian culture and spiritual values in the West has led to the development of a number of societies devoted to the study and practice of Buddhism. Zen has grown in the United States to encompass more than a dozen meditation centers and a number of actual monasteries. Interest in Vajrayana has also increased.

As its influence in the West slowly grows, Buddhism is once again beginning to undergo a process of acculturation to its new environment. Although its influence in the U.S. is still small, apart from immigrant Japanese and Chinese communities, it seems that new, distinctively American forms of Buddhism may eventually develop.

| Special thanks to the Microsoft Corporation for their contribution to our site. The information above came from Microsoft Encarta. Here is a hyperlink to the Microsoft Encarta home page. http://www.encarta.msn.com |

| His Life | Meditation | Doctrine | What's New | Influence | Meaning | Truths | Path | Commandments | Dhamapada |

General

Buddhist Studies WWW Virtual Library: The Internet Guide to Buddhism and Buddhist Studies

http://www.academicinfo.net/buddhism.html

http://www.beliefnet.com/index/index_10001.html

http://buddhism.about.com/mbody.htm

Fundamentals of Buddhism

Fundamental Buddhism Explained

http://www.fundamentalbuddhism.com/

http://www.ship.edu/~cgboeree/buddhaintro.html

http://adaniel.tripod.com/buddhism.htm

Life of Buddha

http://www.miami.edu/phi/bio/Buddha/bud-life.htm

Philosophy

http://www.miami.edu/phi/bio/Buddha/bud-read.htm

Buddhist Studies

http://www.buddhanet.net/l_study.htm

Resources for the Study of Buddhism: compilation

http://online.sfsu.edu/~rone/Buddhism/Buddhism.htm

TEXTS

King Milinda

http://www.miami.edu/phi/bio/Buddha/Milinda.htm

Glossary

Buddhism: A to Z

http://online.sfsu.edu/%7Erone/Buddhism/BuddhistDict/BDIntro.htm

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buddhist

Studies WWW Virtual Library: The Internet Guide to Buddhism and Buddhist

Studies

Access

to Insight: Readings in Theravada Buddhism

Asian Studies WWW Monitor

Buddhasasana

Buddhism

Depot

Buddhist

Resources LinksPitaka

Buddhist

Studies and the Arts

Center for Buddhist Studies,

National Taiwan University

DharmaNet

International

Engaged Buddhist Dharma Page

Fundamental Buddhism Explained

The

History, Philosophy and Practice of Buddhism

Korean

Buddhism

Korean Society of Indian Philosophy

RainbowDharma

Resources

for the Study of East Asian Language and Thought

Sacred Rocks and Buddhist

Caves in Thailand

Siddhartha

- The Warrior Prince

Sparsabhumi - Buddhist & Indological Studies

Tibetan BuddhistLinks

SACRED TEXTS

Proceed to the next section by clicking here> next

© Copyright Philip A. Pecorino 2001. All Rights reserved.

Web Surfer's Caveat: These are class notes, intended to comment on readings and amplify class discussion. They should be read as such. They are not intended for publication or general distribution.