Chapter 4 : Metaphysics

|

An 8-Year Fight Ends Over a 9,200-Year-Old Man July 20, 2004 By ELI SANDERS

|

|

| SEATTLE, July 19 - The ending of a long

legal battle between Northwest Indian tribes and scientists last week is expected soon to put Kennewick Man, a 9,200-year-old skeleton, into the hands of anthropologists hoping for powerful clues to the mystery of who first populated the Americas. The skeleton, named Kennewick Man after the

southeastern |

|

Scientists eager to study the remains faced off against Indian tribes from Washington, Oregon and Idaho, who called Kennewick Man their ancestor and "the ancient one," and demanded his reburial. For a time, pagan groups also got involved, on the theory that Kennewick Man, whose features in one reconstruction were more Caucasoid than Indian, was descended from ancient Norse people.

But in February, a federal appeals court in San Francisco ruled that the tribes had not proved that the remains were those of an American Indian. Anthropologists say the remains are part of an expanding body of evidence showing that American Indians, long thought to have been the original inhabitants of the Americas, may not have been the first people to live on the continents.

"Current thinking is the Americas were not peopled once," said Dr. Robson Bonnichsen, a professor of anthropology at Texas A&M who is one of eight scientists who sued to prevent Kennewick Man's reburial. "They were peopled a number of times."

As recently as the late 1990's, Dr. Bonnichsen said, the

prevailing belief was that North America was first

populated by a single group of people from the Siberian interior, the ancestors of American Indians. They were believed to have crossed the Bering land bridge about

11,500 years ago, during the last ice age; then, with the melting of vast glaciers that blocked what is now Alaska

from the rest of the continent, these people were thought to have slowly migrated southward.

Recent discoveries like Kennewick Man - skeletons that

appear either too old or too different from American

Indians to have been a part of this group - have led scientists to think the Americas must have been populated

by other means as well, most likely by seafaring people

from northeast and southeast Asia, moving in boats along the Pacific Rim and eventually to North America.

Scientists who have examined the skull of Kennewick Man reported that it had more in common with the Ainu, the original inhabitants of Japan, than with present-day American Indians, making them skeptical that he could have evolved these traits in such a relatively short time had he belonged to the Siberian group from which American Indians are thought to descend.

Dr. Bonnichsen said Kennewick Man was one of about 15 skeletons more than 8,000 years old that have been found in North America, many of them with skeletal characteristics very different from those of Northwest Indians.

"It used to appear that there was only one answer, and a simple answer with not much nuance to it," said Dr. James C. Chatters, a forensic anthropologist who in 1996 was the first to study Kennewick Man, before further study was prohibited by the court proceedings. "What we're seeing now that we're getting a chance to look at these individuals is that the peopling of the Americas is much more complex and nuanced than we'd imagined."

The legal battle over whether Kennewick Man was a tribal ancestor centered around the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which requires remains to be returned to Indian tribes if an ancestral link between the tribe and the remains can be proven.

With the federal appeals court having ruled that there was no ancestral link, Rob Roy Smith, a lawyer for the Colville Tribes of northeastern Washington, said the tribes decided last week not to turn to the Supreme Court, fearing that if it upheld the ruling there would be problems for other tribes trying to claim artifacts and bones they believe to be theirs.

Mr. Smith said he was confident that the Justice

Department, which had sided with the tribes in the case,

would also not pursue the case.

While Mr. Smith said the tribes would seek to set restrictions on the methods of study, Paula A. Barran, a

Portland lawyer who represents Dr. Bonnichsen and the other

scientists, said that issue should be settled soon.

Dr. Chatters said he was eager to study Kennewick Man, in part because he "lived long enough that his bones collected quite a record of his activities." Kennewick Man is believed to have been 40 to 50 years old when he died and to have stood 5-foot-9 to 5-foot-10.

Among other things, scientists want to scrape the plaque off Kennewick Man's teeth to get an idea of his diet, to search his bones for traces of DNA and to compare his skeleton with others.

One thing Dr. Chatters would like to learn more about is a three-inch spear point embedded in his pelvis.

"One of the most intriguing questions is, 'How did that get there?' " he said. "Who threw that thing?"

On a basic level, he said, the answer is: "Someone didn't like him very much." But because the serrated edges of the spear point are associated with groups that have more in common with American Indians than with Kennewick Man, Dr. Chatters wonders whether it is a sign of conflict between early Americans like Kennewick Man and the ancestors of the Indian tribes.

"Is this when we're seeing the arrival of these new folks, the ones we call Native Americans now?" he asked.

http://www.nytimes.com/2004/07/20/science/20skul.html?ex=1091357936&ei=1&en=4609e6e0303f16b1

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company

*******************************************************************************

Digging up new lawsuit

--------------------

As anthropologists gain confidence the 8-year fight to study skeleton is over, a new hurdle emerges

LOS ANGELES TIMES

August 3, 2004

SEATTLE - For a few days last week, the United States' top forensic anthropologists thought they were finally going to get their chance to study Kennewick Man.

The eight-year legal battle regarding the 9,300-year-old bones, one of the oldest skeletons found in North America, appeared finished after five Northwest Indian tribes decided not to pursue their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The tribes claimed Kennewick Man was an ancestor and should not be desecrated by study.

Two courts ruled in favor of the eight plaintiff scientists who believe the bones - discovered in 1996 along the Columbia River near Kennewick, Wash. - could yield insights on the earliest inhabitants of the Americas. The skeleton was found to have some Caucasian features, suggesting groups other than Asians may have migrated to the continents thousands of years ago.

But soon after the scientists' apparent victory, a new legal obstacle emerged late last week, this time from the federal government.

New litigation possible

The Army Corps of Engineers, which has custody of the skeleton and which sided early on with the tribes, has objected to so many aspects of the scientists' study plan that new litigation is probable, according to the scientists' attorney.

The earlier battles focused on whether Kennewick should be subjected to scientific study. The new battle will be about how his bones will be studied.

"This case is long from over," said Alan Schneider, a Portland, Ore., lawyer representing the anthropologists. Schneider said the government is using the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979, which empowers the owners of archaeological finds, to hinder the scientists' plan of study.

Schneider predicts that he will have to go to court "to compel the government" to hand over the skeleton. "That seems to be the direction we're heading." Jennifer Richman, an attorney for the Army Corps of Engineers in Portland, would say only that the scientists' plan was "subject to reasonable terms and conditions."

The tribes also want to have a say in how the bones are studied, hoping to minimize "destruction of tissue" and the "desecration of the remains," said Debra Croswell, a spokeswoman for the 2,500-member Umatilla Tribe in Oregon.

Along with the Umatilla, the Nez Perce, Yakama, Colville and Wanapum tribes also claim Kennewick Man as an ancestor. The tribes refer to the skeleton as "the Ancient One."

But a U.S. District Court in Portland and later a federal appellate court said the tribes failed to prove an ancestral link to the skeleton. The deadline to appeal the case to the U.S. Supreme Court was July 19.

What's at stake

Kennewick, made up of more than 350 bones, is being kept at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle.

Scientists believe the bones belonged to a man who stood about 5-foot-9, suffered a severe spear wound to his hip, and was 40 to 50 years old when he died. The man, according to one reconstruction, had more angular facial features than those typically associated with American Indians.

The skull resembled those of Polynesians or the Ainu, the original inhabitants of Japan, whose features were more Caucasoid, scientists say.

The discovery caused a stir, not just among tribes, whose identity as the continents' "original" inhabitants seemed jeopardized, but also among scientists whose long-standing theory on how the Americas were populated was turned on its head.

As recently as the mid-1990s, the prevailing theory was that North and South America were first populated by people from the Asian interior who crossed the Bering land bridge about 11,000 years ago.

Kennewick Man and the recent discoveries of ancient skeletons in South America seem to suggest that the continents were populated by several waves of early migrants who used different routes.

George Gill, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Wyoming and one of the plaintiffs in the Kennewick Man case, said evidence indicates that seafaring people from Southeast Asia or Polynesia could have reached the Americas by traveling along the Pacific Rim, landing somewhere in what is now South America. He said an ancient European people could also have reached the northeast corner of North America.

To believe that the early inhabitants of the Americas all came from the same place "has always seemed a little too simple for me," Gill said. American Indians, he said, show a remarkable variety of physical features. And differences in tools, artifacts and cultural practices between tribes also suggest different origins.

Most of the "new thinking" on how the Americas were populated has not reached the public yet, remaining in the domain of a small group of scientists. Gill said this is partly because the discoveries are coming so quickly, and the theories changing so rapidly, that scientists can barely keep up.

A decade or two from now, he said, the scientific community will likely have a radically different view on the "original" inhabitants of the Americas.

"Most of us in this line of plaintiffs already have gray hair," Gill said. "The way it's going, we may not be around long enough."

Copyright (c) 2004, Newsday, Inc.

This article originally appeared at:

http://www.newsday.com/news/health/ny-hskin033916414aug03,0,4634537.story

------------------------------------------

New York Times July 19, 2005

A Skeleton Moves From the Courts to the Laboratory

By TIMOTHY EGAN

SEATTLE, July 18 - The bones, more than 350 pieces, were laid out on a bed of sand, a human jigsaw with ancient resonance. Head to toe, one of the oldest and best-preserved sets of remains ever discovered in North America was ready to give up its secrets.

After waiting 9 years to get a close look at Kennewick Man, the 9,000-year-old skeleton that was found on the banks of the Columbia River in 1996 and quickly became a fossil celebrity, a team of scientists spent 10 days this month examining it.

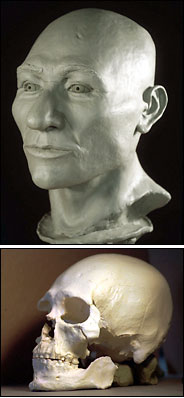

They looked at teeth, bones and plaque to determine how he lived, what he ate and how he died. They studied soil sedimentation and bone calcium for clues to whether he was ritually buried, or died in the place where he was found. They measured the skull, and produced a new model that looks vastly different from an earlier version.

And while they were cautious about announcing any sweeping conclusions regarding a set of remains that has already prompted much new thinking on the origins of the first Americans, the team members said the skeleton was proving to be even more of a scientific find than they had expected.

"I have looked at thousands of skeletons and this is one of the most intact, most fascinating, most important I have ever seen," said Douglas W. Owsley, a forensic anthropologist from the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History. "It's the type of skeleton that comes along once in a lifetime."

He said the initial job of the team was to "listen to the bones," and the atmosphere, judging from the excitement of the scientists as they discussed their work, was electric.

Dr. Owsley said answers to the big questions about Kennewick Man - where he fits in the migratory patterns of early Americans, his age at the time of death, what type of culture he belonged to - will come in time, after future examinations.

"But based on what we've seen so far, this has exceeded my expectations," said Dr. Owsley, leader of the 11-member team and one of the scientists who sued the government for access to the bones. "This will continue to change and enhance our view of early Americans."

In preparation for the initial examination, the hip and skull were flown to Chicago, where they went through high-resolution CT scans, much more detailed than hospital scans. Those three-dimensional pictures were used to produce casts and replicas of the bones.

|

For now, the team has finished what amounts to a sort of autopsy, with added value. To that end the examination, which took place under extraordinary circumstances at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington, was aided by a forensic anthropologist, Hugh Berryman of Nashville, who often assists in criminal investigations.

"This is real old C.S.I.," said Dr. Berryman, referring to the crime scene investigations that inspired the hit television shows.

The skeleton caused a furor from the time of discovery, making waves far beyond the academic realm, after an examining anthropologist said it appeared to have "Caucasoid" features. One reconstruction made Kennewick Man look like Patrick Stewart, the actor who played Capt. Jean-Luc Picard in "Star Trek: The Next Generation."

American Indian tribes in the desert of the Columbia River Basin claimed the man as one of their own, calling him the Ancient One. The tribes planned to close off further examination and to bury the remains, in accordance with a federal law that says the government must turn over Indian remains to native groups that can claim affiliation with them.

A group of scientists sued, setting off a legal battle, while the bones remained in the custody of the Army Corps of Engineers.

In 2002, a federal magistrate, John Jelderks of Portland, Ore., ruled that there was little evidence to support the idea that Kennewick "is related to any identifiable group or culture, and the culture to which he belonged may have died out thousands of years ago."

The ruling, backed by a federal appeals court last year, cleared the way for the scientists to begin their study.

After being dragged into the culture wars, Kennewick Man remains a delicate subject - something that was clear in how the examining scientists parsed their descriptions of the skull at the end of 10 days of study.

David Hunt, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian who was instrumental in remodeling the skull, said he was sure there would be criticism of his reproduction, but he said it was based on the latest and most precise measurements of the head. He said it was accurate to within less than a hundredth of an inch.

Standing by the translucent model inside the Burke, Dr. Hunt said, "I see features that are similar to other Paleo Indians," referring to remains older than 7,000 years that have been found in North America.

But his colleague at the Smithsonian Dr. Owsley said that term was imprecise.

"It should be Paleo-American," Dr. Owsley said. "These bones are very different from what you see in Native American skeletons."

Earlier, other anthropologists said that Kennewick Man most resembled the Ainu, aboriginal people from northern Japan. The scientists who examined Kennewick Man this month did not dispute that designation, but they said fresh DNA testing, carbon dating and further examinations would give them more accurate information.

Earlier DNA testing, done during the court cases, failed to turn up matches with contemporary cultures.

One key to Kennewick Man's life and times will be the stone spear point that was found embedded in his hip bone. Dr. Owsley said it was clear that the man did not die of the projectile, which had been snapped off.

"This was a healed-over wound," he said.

But the spear point, which was made of basalt, will be the guiding clue as anthropologists seek a match to other cultures.

Kennewick Man's discovery brought fresh vigor to the discussion over how the Americas were inhabited. Earlier theories held that people crossed a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska. But Kennewick Man, along with a few other findings, suggested that there were waves of migration by different people, some possibly by boat.

The scientists who examined the skeleton, and their supporters, still fear that a political move could cut off future study. On behalf of several tribes, Senator John McCain, Republican of Arizona and chairman of the committee that controls Indians affairs, has introduced an amendment to the law the governs custody of ancient remains.

His proposed change would broaden the definition of Native American remains, expanding it to well into the past. Indians say such a change is needed to protect ancient ancestors, while others say it will make it nearly impossible to study ancient remains, even if they have little or no connection to present tribes.

But as the scientists finished their 10-day study of Kennewick Man, with plans to report the results in October, the politics for once seemed to take a back seat to the giddiness of discovery.

"This is like an extraordinary rare book," Dr. Berryman said, "and we're reading it one page at a time."

Return to the previous section Post Modrenism.

Introduction to Philosophy by Philip A. Pecorino is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Return to: Table of Contents for the Online Textbook